There are a wealth of books on writing out in the world, from the good to the bad to the absolute nonsense—and a lot of them are by writers of speculative fiction. “Writers on Writing” is a short series of posts devoted to reviewing and discussing books on the craft that were written by SFF(&H) authors, from John Scalzi to Nancy Kress. Whether you’re a beginning writer, a seasoned pro or a fan, these nonfiction outings can be good reads.

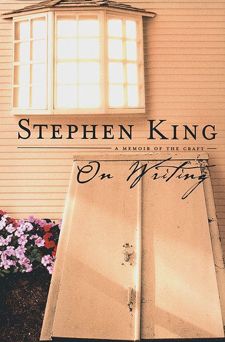

One of the most popular books on the craft is undoubtedly Stephen King’s memoir/writer’s book, On Writing. As a text it serves several purposes: it’s partially a collection of personal anecdotes, partially a candid memoir, partially a guidebook and partially a sort of advice column for new writers. Where many craft manuals read like dry textbooks, On Writing is luxurious. It pulls you in as if you’re having a conversation with King about the work and his life in some quiet, pleasant place; possibly over coffee.

It’s hard not to love a book that feels both personal and informative, that teaches while pleasing the reader on a deeper level. However you might feel about King’s fiction, he has a gift for talking about the process.

I first encountered On Writing when I was thirteen or fourteen years old. I had hit the critical point where I realized that I didn’t just like telling stories, I loved it, and I wanted to do it for a living one day. Coincidentally, I was also a bit of a Stephen King junkie. I found him fascinating because some of his books where great, knocked right out of the park, but others were—and I say this with all respect—pretty damn awful. (King acknowledges that he has penned some real stinkers in On Writing, which makes me like him all the more.) So I bought his book about writing. I remember that I read it in one sitting; that may or may not be right, but it probably is. I do know that I felt like I had learned more in that one day, in a way that I could actually articulate, than I had in my entire life. The multi-layered toolbox is still how I picture the basic skills of the craft.

I’ve since owned about six copies of it, all in varying stages of disintegration, and it has never let me down. Which isn’t to say that it’s perfect; there are a few things in it that I not only disagree with but which will seem vaguely insane to anyone working in the publishing world right now, like his thoughts on manuscript length. On the other hand, those few things which are no longer quite correct are almost inconsequential next to the wealth of good advice and information. I can’t promise objectivity when it comes to this book. I love it too much. I can, however, tell you why I feel so strongly about it.

As I said in the review of Scalzi’s You’re Not Fooling Anyone […], biographical sections in these sorts of books don’t necessarily offer any actual advice on the craft. The first third of On Writing is a set of snapshot-stories about King’s life from childhood on, a sort of “how I got here” story. At first it seems fun but not terribly important (from a learning-about-writing perspective), until he begins to discuss his professional beginnings and the progress of his career. Then the reader will notice that there is advice hidden in the stories, which become more personal and reflective as the section goes on—how to deal with rejection, how to manage a life with writing in it when you’re working overtime at a tough job and don’t have the money to support your family, then how to write if you’re teaching and it seems like all the soul has gone out of it; those just to name a few. The memoir section isn’t just a memoir, engrossing through the personal stories are, it’s an example of how one man found himself the writer he is today.

There’s a gem in the memoir section, as well: King’s destruction of the alcoholic-writer stereotype. He’s been there, he’s done that, and he can talk honestly about the consequences.

Hemingway and Fitzgerald didn’t drink because they were creative, alienated, or morally weak. They drank because it’s what alkies are wired up to do. Creative people probably do run a greater risk of alcoholism and addiction than those in other jobs, but so what? We all look pretty much the same when we’re puking in the gutter.

The glamorous image of the distraught alcoholic writer lingers in the corners of the literary world. It’s romantic, but the real thing isn’t, and King puts that across as clearly as he possibly can.

Then, he gets to the meat of the book: the actual writing chapters.

These chapters alone justify the purchase of this book and multiple re-readings. No matter your “level,” you will benefit from King’s walkthrough of the craft from the basic grammatical toolbox to things like theme and symbolism. He starts at basic construction and works his way up piece by piece to the most abstract and difficult to master elements of fiction without ever breaking stride. His examples are universally understandable and often humorous, demonstrating how to not do certain things but also how to do them properly through contrast.

Whether or not you’re a fan of King’s fiction, his grasp on the craft and what it takes to do the job is impeccable. His admission that he often falls short on all of the principles, and so does everyone, is comforting.

There are a few things that I object to in the course of the writing chapters, though. The most obvious is that he comments offhand that 180,000 words is a reasonable length for a novel. As anyone who has done even the slightest amount of research into the upper limits of what an agent or editor will look at will tell you, that is completely wrong. Selling a tome that capable of killing a small dog is nearly impossible in today’s market unless you’re a wildly successful epic fantasy author (or, Stephen King). 100,000 is more like it, and depending on the genre, the writer may end up close to 80-90,000.

Not to mention, the thought of having to construct a 180,000 word manuscript is enough to make most beginners break out in terror-hives.

The other point I’ll disagree on is King’s dislike of outlining. He doesn’t approve of or trust plotting and says that instead discovering a book should be like unearthing a fossil one careful discovery at a time—and I don’t find that last part objectionable. However, many writers (myself included) find that fossil not during a rough draft but by spending months on scribbling notes and outlines. It doesn’t make the process any less organic, as King claims. It feels much the same as drafting off the cuff; actually, in my case and that of other writers I know who outline, the story is still a fossil. We’re still slowly discovering the tale and engaging with its growth in the same way, it’s just that we aren’t putting the actual book into the precise words until we’re ready to do so. Personally, I find that I like to have the story almost entirely written in my head before I take it down on paper.

But, that’s personal. Everyone writes a different way and has a different favorite method, a different way to feel at home and in love with their story. King’s isn’t to outline, and mine is. I don’t think that his insistence that plotting and outlining steal the joy of the work is accurate as advice—it might be for him, but it isn’t universal.

The craft section is still nearly perfect, despite those two points of contention. While he’s teaching grammar and explaining sentence variation, King never manages to sound like a textbook. His voice is always as clear as possible and as personal as possible, no matter whether he’s discussion his addiction recovery or how to use dialogue. That’s invaluable because it makes the content easier to enjoy, and content that’s easy to enjoy is easy to remember. The lessons of On Writing stick because they’re well-told, not just because they’re great advice.

The book rounds out on a discussion of King’s infamous accident and near-death. It’s a perfect bookend to the first third of the book, which dealt with how he became the writer he was. The end is about how writing benefits the writer and how to live life as fully as possible no matter the circumstances. It’s touching and real. The final lines sum up the gist of the book with resonance: “Writing is magic, as much the water of life as any other creative art. The water is free. So drink. Drink and be filled up.”

There are also codas to the text: a story pre- and post-revision to give the reader an idea of how a revision should look and a reading list of books King enjoyed or thinks demonstrate the craft particularly well. These objective portions are a nice bonus addition to the central ideas of the book: read a lot, write a lot, and don’t stop.

I cannot recommend On Writing enough. It’s splendid. It isn’t the only craft book I love, and a reader should never stop with one, but I—personally, in my heart of hearts, so to speak—think this is the most valuable for a new writer. Its advice is necessary, concise, and engaging. Don’t skip On Writing.

Next: Booklife by Jeff Vandermeer.

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.